Making Mozart

Why attention is the only form of education that matters.

The incidence of genius talent like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart has been in rapid decline since 1400:

Let’s see how genius unfolded in Mozart’s childhood to understand why.

Amadeus Mozart played his first chord when he was four years old - which he taught himself.

One evening, watching his sister practice her scales like most other evenings, Amadeus wandered over to the piano, which often captured the attention of the people he loved. His sister and his father watched as he approached the stool. He reached out a hand and copied what he had seen his sister do so many times: he made a chord.

He likely saw an expression of awe from his sister and father. In his brain, no doubt, millions of connections were being formed to cement his love for music that would change the world forever.

At that time in Salzburg (where the Mozarts lived), the state required all children to attend school. But Leopold – Mozart, the elder – applied for an exception because school wasn't what young Mozart needed most.

Leopold helped four-year-old Amadeus Mozart learn to play the piano. At five years old, Amadeus composed his first piece. By six years old, he and his sister had begun traveling the world together as child prodigies, with their entire family.

When Mozart was nine, he was playing harpsichord for royalty, when he suddenly stopped to go pet a cat that had walked into the room. He was a genius, but he was still nine, after all, and those around him allowed him to be both nine and entirely himself.

These days, family investment in education looks more like getting to the bus on time than playing piano together. We no longer trust ourselves to know what is best for our child — even if it were to present itself as clearly it did in the case of Mozart. Unfortunately, the social pressure to not let our kids “fall behind” is just too great. It takes courage to raise kids in non-state-approved ways, even if we have rising evidence that families and communities are far better at raising happy and smart kids than institutions are.

The things that kids put their attention spontaneously on are the things kids learn about most easily. That attention is often innate, but it can also be directed by the loving attention of parents, mentors, and tutors – or by the environment these guardians create. In the case of Mozart, his attention was encouraged by his father's interests, and his environment was steeped in music – which just happened to map very nicely with his own inborn talents.

The ideal education is one where we’re paying attention to what our kids are paying attention to. We’re noticing what lights them up, their strengths and weaknesses and shortcomings, and we’re building their education around that – and around their innate internal compass.

In the education system, kids’ eyes go wide with no one there to notice. We cram them into boxes where their passions wither and die.

We have lost faith that our attention could educate our kids to be not only “normal” (whatever that is) but great.

Ideally, there are a few types of attention to pay:

Attention you pay to your kid

Attention your kid pays (what lights them up)

Attention fostered by your kid’s environment (like Mozart’s house full of music)

Education is attention

In constructing education systems, we’ve gotten confused. It was never about getting the information right. The “right” information is always changing anyway: 100 years ago, scientists assured us that cigarettes and leaded gasoline were perfectly harmless. The career your kid will be working in 30 years from now doesn’t even exist yet.

No, the point of education was always about attention – paying attention to your kid, and directing what they pay attention to (by both your actions and their environment).

Mozart was well-educated, not because he had all the “correct” information in textbooks, but because he was given the right attention: he was paid attention to, his growing attention to music was fostered, and the environment he lived in made his passionate attention feel worthwhile. He didn’t need to read a textbook about the newest principles of natural philosophy; he was meeting the greatest minds of the time on his travels from castle to castle.

Now, of course, we don’t all get to be famous court musicians making friends with famous artists and scientists. But there are paths to greatness for each of us. Take, for example, Cole Summers, whose blue-collar parents gave him the attention and freedom to explore his education on his terms. In many ways a normal kid, he was inspired by YouTube videos of Warren Buffet, and by 9, he bought a 350-acre farm to raise goats. That’s not an act of genius, but an act of boldness and an embodied engagement with the world, fully supported by his parents.

Summers’ and Mozart's upbringing was nothing like modern education, where children are placed in centralized classrooms and taught abstract subjects and assured that their passivity will translate into active adulthood… one day.

Mozart’s father taught him the basics for his day: literature, mathematics, and even dance – but in the context of the real-world experiences Mozart was having. Summers learned mathematics and writing, but in the context of the entrepreneurial goals he was hungry to set.

This all comes back to attention. Both parents were paying attention to what their kids cared about (and directing their attention by the milieu they’d established), and because of this, were able to iteratively create an education that was tailored to the kids’ specific interests and goals (and by doing so, allowed room for greatness).

Attention is the greatest currency in a child's life – not just the attention we pay to them, but what they pay attention to themselves. Every parent knows how closely kids watch us, copying our phrases and gestures to our delight (and sometimes horror).

Children also are extremely sensitive to what we value – the time we spend playing the family’s piano, the books we display in the home, and whom we have over for dinner. In Mozart’s case, he watched as his sister worked hard to play the piano, and he watched as his father encouraged her. Wanting that attention, he played his first chord at four years old. His family's positive attention and praise cemented Mozart's curiosity and passion for music. And, thanks to that powerful moment, we still hear Mozart's influence on the music we all listen to today.

Here’s where people get tripped up. Yes, the environment Mozart grew up in created a world-shaking genius. But parents should not try to copy it in hopes of a particular outcome. Not even Mozart knew he would become Mozart. He had to chart that path himself.

The goal is to make an environment as close to ideal as you can manage. That is what will create strong, creative kids who can tap into their genius – not sending them to a nondescript building to become nondescript people.

Your ideal environment is going to be unique to you and your family. It’s going to involve investing your time, attention, and money in the activities and objects that align with your values. Kids pay attention to and learn from what’s available to them.

A beautiful education matters more than geniuses produced – a high incidence of genius in a population just happens to be a good marker for a positive education environment. The point isn’t necessarily to make more geniuses, but fewer geniuses overall indicate that we’re doing it wrong (see: graph at the opening).

What really matters is the small details of everyday life that add up to meaningful context for children's education: the smell of cooking, the hollering of siblings, and the appreciation for the song your son wrote. Access to nature, art supplies, playgrounds, libraries, museums, street festivals. That all contributes to a stimulating environment that can encourage children to be their best selves. It doesn’t mean they will change the world, but they have the best chance when raised within their specific context.

All childhoods of exceptional people have that in common: they were specific to their time and place. They grow from their own soil. They cultivated the beauty that they had access to. That applies to the rich, in the case of Mozart, but also to the less-well-off, in the case of Summers.

What unites them is the environment that best represented the things they valued most deeply, and raising children there. It was never perfect, and that was really the point. Modern school makes the mistake of trying to be perfect, with white walls, rows of desks, and standardized textbooks. A good education is on the soil of the specificity of the child's family. Paradoxically, grounded imperfection is closer to “perfection.”

Your kids, to the extent they are truly curious about the world around them, don’t care about getting an “elite quality education” to brag about. They will gladly accept less polish if it means they get more attention from you, their mentors, the community, etc.

Children need attention to survive, and the specific attention they receive from their parents and caregivers can motivate them to become curious, passionate, and successful. The disregard and dehumanization they receive in school is surely not good for their wellbeing and is, at the very least, a contributing factor to the decline in genius worldwide.

Parents should be less concerned about “falling behind” in the “keeping up with the Joneses” sense, and more concerned with crafting a beautiful childhood.

You can only give kids personalized attention in a home or community that cares about them.

He was a musical genius only in hindsight

It’s easy to look back and say, “Well, yeah, easy for that dude to pull his kid out of school – he was literally Mozart.” But his father didn’t know that. “Mozart” was nothing more (yet) than the family name. He took a risk on raising his son the way he felt would best encourage the genius he could sense, but even he wasn’t certain where it would lead or what it would become. The same is true for Cole Summers’ family – they didn't know how great their son would be. They just kept trusting the positive indicators.

What’s incredible about Leopold Mozart is his leap of faith by betting on his children and going against what was “socially acceptable” in Austria at the time. Leopold had to go out and convince the schools to let him educate his kid.

We want to make the following points carefully:

Genius arises in ways that we have very little control over

Making the next “Mozart” wasn’t even Mozart’s father’s goal

You can’t plan for the moment your four-year-old makes a chord on the piano and cements his love of music for the rest of his life. You can't predict that your kid will fall in love with robotics, or acting, or insects. You couldn’t replace that with years and years of AP courses and tutors. In the natural course of a beautiful childhood, miracles of coincidence tend to pop up — if you are paying attention.

To illustrate that more clearly, let’s look at another world-changing musician. Paul McCartney’s father encouraged Paul to take music lessons when he was 11, but Paul preferred to play by ear. Then, his father encouraged him to audition for the Liverpool Choir, but he didn’t get in. Finally, he gave Paul a nickel-plated trumpet. But when rock-n-roll became popular, Paul traded his father’s instrument for a guitar. The rest is history.

There is just no way to “make” his son Paul become a great musician. It happens – but it happens because his father took an interest, paid attention, and tried different approaches with his son, even as the specific attempts “failed.”

That’s what happened with Mozart, too – and you can see what resulted from a childhood of freedom, curiosity, and beauty. That’s what’s difficult to understand about genius in hindsight. True moments of genius are like cosmic bursts that come from the interplay of what’s inside a child and what’s available around him; you can’t force them or will them to happen. You have to watch for them.

Without permission to grow from the soil we are planted in, a genius like Mozart is impossible.

Genius is zero to one

School trains our population to be good at making what already exists – more and faster.

An “F” is a stain on your permanent record, not a necessary lesson on the way to success. Thus, fear of failure is deeply ingrained in our culture. We take fewer risks necessary to leap from zero to one — less genius.

Lesson plans are all about getting kids to reverse-engineer what is already understood and then having their understanding scrutinized by a multiple-choice test. On the other hand, Mozart, Cole Summers, and McCartney stepped beyond lesson plans into a world where their creations become the lesson plans for others. They went from zero to one, a metaphorical leap from nothing to something, while school teaches you only how to go from 1 to 1+n – simply making more of what we already know.

Creative geniuses have intuited this mismatch since the proliferation of the modern school system, and thus the “cool kids” know that “school sucks.” Cutting-edge scientists tell young people to “drop out.” Tech entrepreneurs offer 100k for kids to quit school. “Ivy League dropout” is practically a bragging point on resumes in Silicon Valley.

But those are tiny subcultures compared to the culture at large. There is still a sharp divide: are you a school person? Or are you rock n’ roll?

Famously, modern artists like Kurt Cobain die at around 27. As we’ve seen in our examples, genius tends to come early to those willing to take the ride. Today’s musical geniuses tend to live degenerate lifestyles because modern society has no formal structures to foster their education. So, they go underground, which usually happens to be a place full of drugs and vice.

For most modern kids, it’s either “stay in school” or “sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll.” Not enough exists in between. Clearly, there is somewhere in between, though, because Mozart was there. Cole Summers, too. And they both started very young.

Most of the years of extreme genius happen at an early age. In modern life, we see genius happening later and later and less often. We’re overeducating and underachieving. In all the examples we explored, these exceptional people were put into the arena long before they were “ready.” Mozart didn’t take ten classes on music theory before he was allowed to make a chord. He just did it. And he was four.

Society overeducates everyone in our most creative and energetic years. We’ve created a state-funded box for kids, LifeLite. They are only allowed to passively sit in the box of LifeLite, downloading the “correct” information (which, remember, will almost certainly be incorrect in ten years), and then, at 18, or worse, 22, they are finally tossed into “real life.” No wonder more and more people have anxiety disorders, and the world is bereft of genius.

For Mozart, there was no homework, test to pass, or teacher to impress. There was only Mozart and his ability to interact with reality. Does the audience clap or cheer? Does a tear fill someone’s eye as he completes the newest composition? There is no way to study for that exam. You just do it.

That’s the pressure we need to make something great. Nothing more than early exposure to the rules of reality.

The vibe of public school

None of these outcomes are surprising if you know the real history of our education system.

School is expressly not trying to produce geniuses.

Here’s a quote from one of the founders of modern public education:

You can feel it when you walk into a public school classroom. What is the mood there? Is there a spirit of learning? Are their kids of all ages debating their favorite writers? Are they being paid attention to?

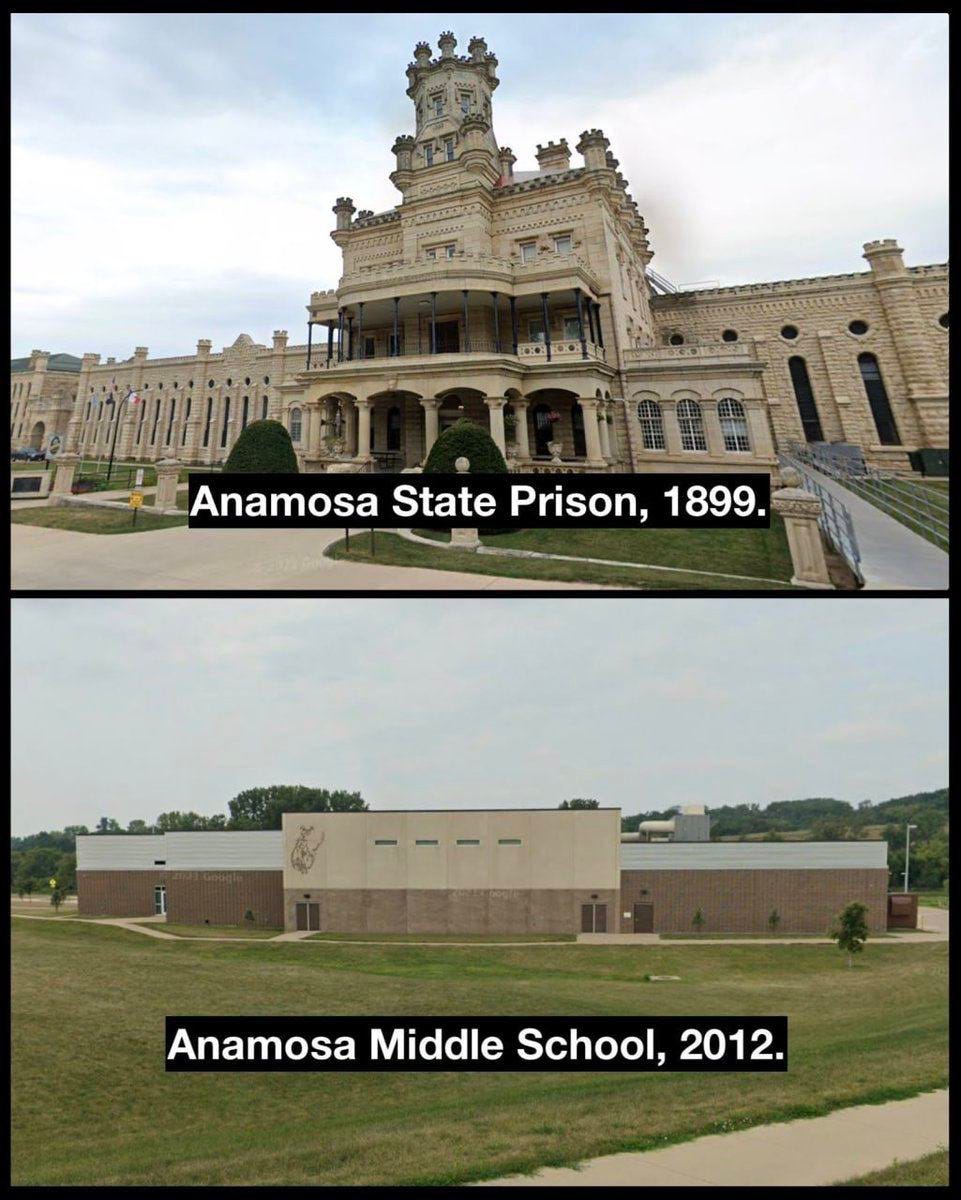

Or, does it more readily remind you of a state prison – or, in the best-case scenario, the DMV? Think of how Mozart's environment shaped him and his future; now imagine how public school shapes kids.

Sometimes our prisons have a higher sense of place and beauty than our schools:

We don't have to speculate about the outcomes. The results are in. Kids are depressed, doing poorly, and not interested in learning.

They’re missing out on contextual education because no one notices them. The attention of both teacher and student is being institutionally guardrailed into predetermined lanes, which is the opposite of how you create a genius – or a happy child.

But don’t get it wrong: the point is not to raise the next musical genius. The point is to get your kid to embody their specific genius. That could be to be a homemaker, a reliable provider, an entrepreneur making a change in their local community, or a lynchpin in a growing startup. There are many ways your genius can be embodied, and lots of them don’t even exist yet

The public schools tried to scrub the world of home and hearth, and they succeeded. As a result, there is less genius in the world than there should be.

It's time parents and communities encouraged each other to raise kids in “radical” new (read: old) ways.

Thanks for reading,

Taylor + rebelEducator team

What we’re published this week:

The American myth of illiteracy: how education worked before taxpayer-funded schooling

Fantastic essay and something that I have tried to pursue with my sons in the 5 years we have been homeschooling them.

This was really good reading.