The dark history of upside-down education

We’re bottom-up learners, and the school system is top-down.

It’s the late 1920s. Soviet-Russian neuroscientist Lev Vygotsky travels to pre-modern parts of Asia for an important test.

He shows the tribal folks a hammer, a saw, and a log. He asks, “which is not like the others?”

When they don’t understand, he explains, “The log is not like the others, see? It’s not a tool like a hammer or a saw.”

The tribal people smile and say, “Yes, but you need the saw and the hammer to do something with the log.”

He then shows them shapes, like a circle, a triangle, and a square. “What are these?”

“A bowl,” someone says, pointing to the circle. “An arrowhead,” pointing to the triangle. “And a house,” to the square.

Vygotsky sighs and concludes that primitive people have no ability for abstract thinking.

The “primitive” people probably conclude that Vygotsky is insane.

In Vygotsky’s motherland, children are taken from their parents at an early age and placed in a school where they are forced to learn abstract concepts most of the day. They don’t learn about bowls and arrowheads – they learn about circles and triangles.

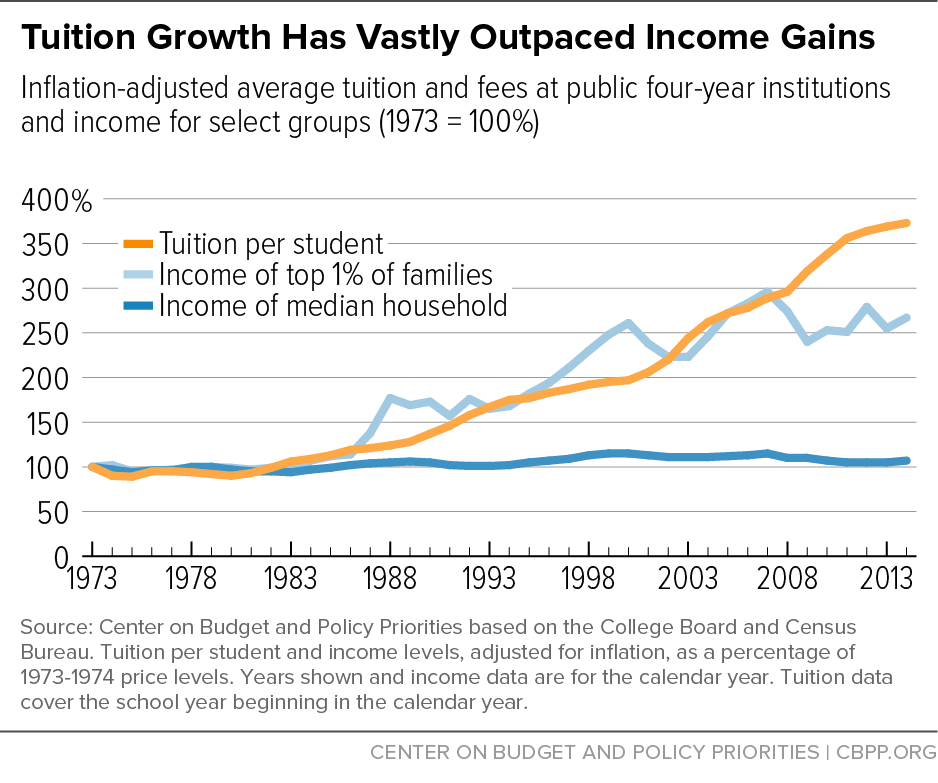

But, left alone, humans learn things through context.

You can’t erase context

Humans are contextual.

You can't perceive light without darkness, big without small, happy without sad. The context always influences whatever you’re looking at, whether you know it or not.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg.

You can't see the world without your body, nor can you understand your community without your family or your nation without your community.

We are Matryoshka nesting dolls of perception. Everything depends on everything else. We come into this world by first understanding our mother, then our father, then our family, and so on. Everything we learn after that is based on our initial reference point.

But we live in the modern world, right? Do we need to train people to think more abstractly now?

In the article “Childhoods of exceptional people,” Henrik Karlsson explores what exceptional kids have in common: dedicated tutors, play, and freedom. But another factor is not directly referenced in the piece: these exceptional children were deeply embedded in their family, community, and culture. Virginia Wolfe, for example, grew up, as “most of the literary people of mark . . . clever young writers and barristers, chiefly of the radical persuasion . . . we used to meet on Wednesday and Sunday evenings, to smoke and drink and discuss the universe and the reform movement.” Even if they moved far away, most were always trying to find their “place” in the world. Pascal was rushed to Paris when he showed aptitude in math. The entire family picked up and went with him. “The instinct was to curate a culture, not to teach, not primarily.” That context motivated them to be interested in everything they would eventually master – from writing a letter home to the heights of mathematics.

What these children had was more like what the natives had – not the Soviet scientist, whose education was in a sterile classroom far away from his family.

If kids want to flourish truly, they need to understand why what they’re learning matters. In other words, why should they care? When a circle is always just a circle and never a bowl – or the brim of a hat, or the radius of an apple – kids naturally tune out.

How often are kids asking, “When am I ever going to use algebra in the real world?” If you’re shoving them in a sterile classroom while a stranger writes esoteric symbols on a whiteboard, of course any sane child will wonder, “what does this have to do with me?”

By creating a top-down school system that imposes its values and curriculum and is context-free, we have destroyed what makes kids interested in learning in the first place.

We can re-capture passion for learning. But first, we have to understand the depth of the problem.

The state of state school

The current school system seeks to remove these vital-yet-hard-to-measure layers of context (like family, for example) and replace them with a "formalized" system of beliefs and concepts administrators deem universally acceptable.

It does this by necessity and because it’s convenient. It must allow for all types of people and their different contexts, cultures, and backgrounds. It also means that you can standardize measures, distribute government funds, and, if you’re feeling spicy, control your population.

The modern curriculum we now take for granted was put together upside-down from the beginning.

But everything interesting humanity has learned over the centuries was from bottom-up, contextual explorations. Read any biography of a great philosopher/scientist/artist, and you will see a life full of contextual meaning around their field of study: mentors who took them under their wing, parents who read books to them, and friends who challenged them.

Examples of this philosophy of learning with action include dropping an apple to understand gravity or swinging a pendulum to understand the conservation of motion. But, deeper than that, kids need mentors and environments that make it tangible why knowing abstract things would matter to them.

Bizarrely, the school system takes these accumulations of bottom-up human endeavors and tries to impose the concepts into our kids' brains, top-down. Don’t worry about the bowl – just focus on the circle. Kids have no idea why they should care. And, honestly, they shouldn’t. The problem with curricula is that, again, we are contextual creatures who will always see the world from our particular place in it. That’s how all great ideas were originally discovered. That’s the way kids become passionate about anything.

By removing the story and trying to make the curriculum "objective” and therefore sterile, schools have destroyed the kid's personal relationship with learning. A huge price to pay for the benefit of standardized measurements – which are a big driver of how school currently works (and gets funding).

On top of all of that emotional catastrophe, cramming in the top-down knowledge doesn’t stick. For example, not a single student in 53 schools in Illinois can do math at grade level:

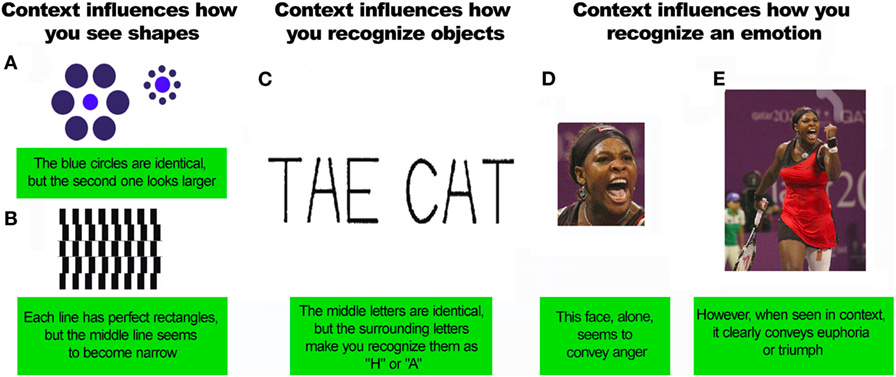

Do we just need more money for better books, teachers, and technology? Money doesn’t buy results. Tuition continues to go up while test scores (and, later, income) continue to drop:

In the context of institutional schools, most kids are not interested in learning.

What about the few who do learn (or, at least get high grades) in these contexts?

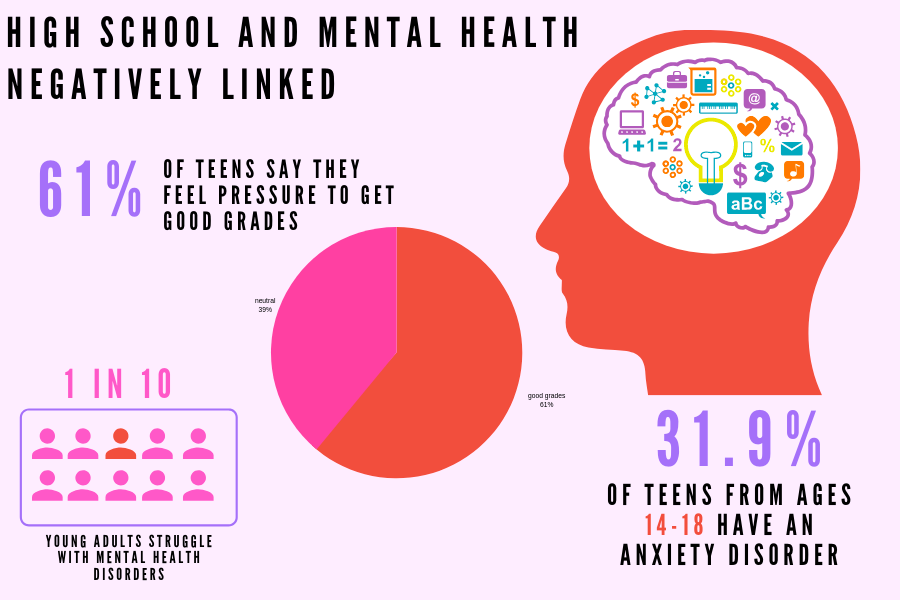

Kids who are so anxious they force themselves to cram the context-free curriculum into their heads, no questions asked, also deserve our concern. Anxiety disorders are through the roof in these schools, too:

We’ve gone against the natural order by forcing kids into learning things with no contextual bearing on their lives.

The unintended consequences of this decontextualization are far-reaching.

The kids won’t sit still

Kids don't feel a real-world connection with what they are learning.

The resulting miseducation not only fails to teach practical skills, like how to make money, but also fails to teach them an appreciation for beauty and enterprise that would inspire them to start a successful business in the first place. In other words, it simultaneously fails to get kids' feet on the ground AND their heads in the stars.

Kids don’t hate learning – they hate school. Instead of trying to fix the education system, we drug all the kids who to refuse to sit still in this perverse purgatory.

The result of this brainwashing, so to speak, is evident everywhere in our culture. And it's always in the same fashion: we think the world is made of parts that can be easily broken down.

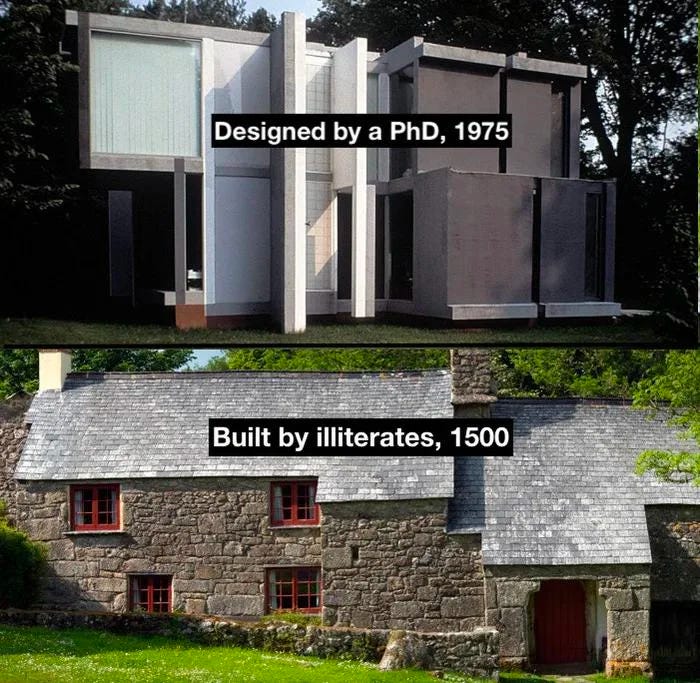

This top-down thinking trained designers and architects, who made the world ugly, proliferating strip malls and billboards. We are taught that nothing you can't directly measure matters, so we discount inspiration and beauty (contextual phenomena). This a tongue-in-cheek example, but it illustrates the point:

We prefer the certainty of quarterly profits – a grown-up’s report card — over anything long-term.

Traditional school is not capable of teaching kids this because it has to do with every aspect of life – not just one “subject.” It requires connection, not segmentation. It belongs to patient mentors, not subject matter experts.

How do you fight this, then?

You have to see (and love!) each kid for who they are and who they can become. That's not easily marked on a scantron sheet. It resists measure. And measurement is all industrialized education has going for it.

At the core of it all, what actually helps kids flourish is at complete odds with the practices of industrial school.

The fundamental disconnect cannot be fixed with more government funding or a new child measurement system.

The solution is in educators, not more systems

Our ability to teach is much greater than our ability to understand how we're teaching and why.

In other words, trust the gut.

Top-down thinking got us into this mess, and more of it will not get us out.

Trying to measure and codify intuitive mentorship into a system that must be forced on children is a fool’s errand – even more than that, it’s a contradiction in terms. We need to give the power of intuition back to educators. We need to let educators and parents choose curricula that work for them – and even experiment with new approaches. Freedom of choice should guide our systems rather than top-down approaches. Let people mentor kids in ways that can't be measured in anything but the kid’s enthusiasm.

To start, empower each other to teach our kids ourselves, build micro-schools, and just let our kids play outside more often. We should judge educators by happy kids, not arbitrary test scores.

“The professionalization of teaching preempts a function that belongs to everybody in a healthy community, and makes things that are inherently easy to learn — like reading, writing, and arithmetic — difficult by insisting they be taught through pedagogical procedures,” wrote John Taylor Gatto, two-time New York State teacher of the year, who publicly resigned on the pages of the Wall Street Journal.

We all have passion for teaching our kids about the world around us. Then we can begin to heal a world made ugly and confused by a philosophy of abstract grades and coerced homework.

Thanks for reading,

Taylor + rebelEducator team

What we published this week:

This is fantastic. So well articulated.

Great job! I was in the high school classroom as a Spanish teacher for 15 years. The only way I passed a student was if he or she could have a conversation with me! Real life context. It really is what matters most.